Climate Change And Extreme Weather Impacts Hit Asia Hard, Long-Term Warming Trend Accelerates

Asia is world’s most disaster-prone region, water-related hazards are top threat, but extreme heat is becoming more severe

The State of the Climate in Asia 2023 report highlighted the accelerating rate of key climate change indicators such as surface temperature, glacier retreat and sea level rise, which will have major repercussions for societies, economies and ecosystems in the region.

In 2023, sea-surface temperatures in the north-west Pacific Ocean were the highest on record. Even the Arctic Ocean suffered a marine heatwave.

Asia is warming faster than the global average. The warming trend has nearly doubled since the 1961–1990 period.

“The report’s conclusions are sobering. Many countries in the region experienced their hottest year on record in 2023, along with a barrage of extreme conditions, from droughts and heatwaves to floods and storms. Climate change exacerbated the frequency and severity of such events, profoundly impacting societies, economies, and, most importantly, human lives and the environment that we live in,” said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

In 2023, a total of 79 disasters associated with hydro-meteorological hazard events were reported in Asia according to the Emergency Events Database. Of these, over 80% were related to flood and storm events, with more than 2 000 fatalities and nine million people directly affected. Despite the growing health risks posed by extreme heat, heat-related mortality is frequently not reported.

“Yet again, in 2023, vulnerable countries were disproportionately impacted. For example, tropical cyclone Mocha, the strongest cyclone in the Bay of Bengal in the last decade, hit Bangladesh and Myanmar. Early warning and better preparedness saved thousands of lives,” said Armida Salsiah Alisjahbana, Executive Secretary of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), which partnered in producing the report.

“In this context, the State of the Climate in Asia 2023 report is an effort to bridge gaps between climate science and disaster risk through evidence-based policy proposals. ESCAP and WMO, working in partnership, will continue to invest in raising climate ambition and accelerating the implementation of sound policy, including bringing an early warning to all in the region so that no one is left behind as our climate change crisis continues to evolve,” she said.

Approximately 80% of WMO Members in the region provide climate services to support disaster risk reduction activities. However, less than 50% of Members provide climate projections and tailored products that are needed to inform risk management and adaptation to and mitigation of climate change and its impacts, according to the report.

The report, one of a series of WMO regional State of the Climate reports, was released during the 80th session of the Commission in Bangkok, Thailand. It is based on input from National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, United Nations partners and a network of climate experts. It reflects WMO’s commitment to prioritize regional initiatives and inform decision-making.

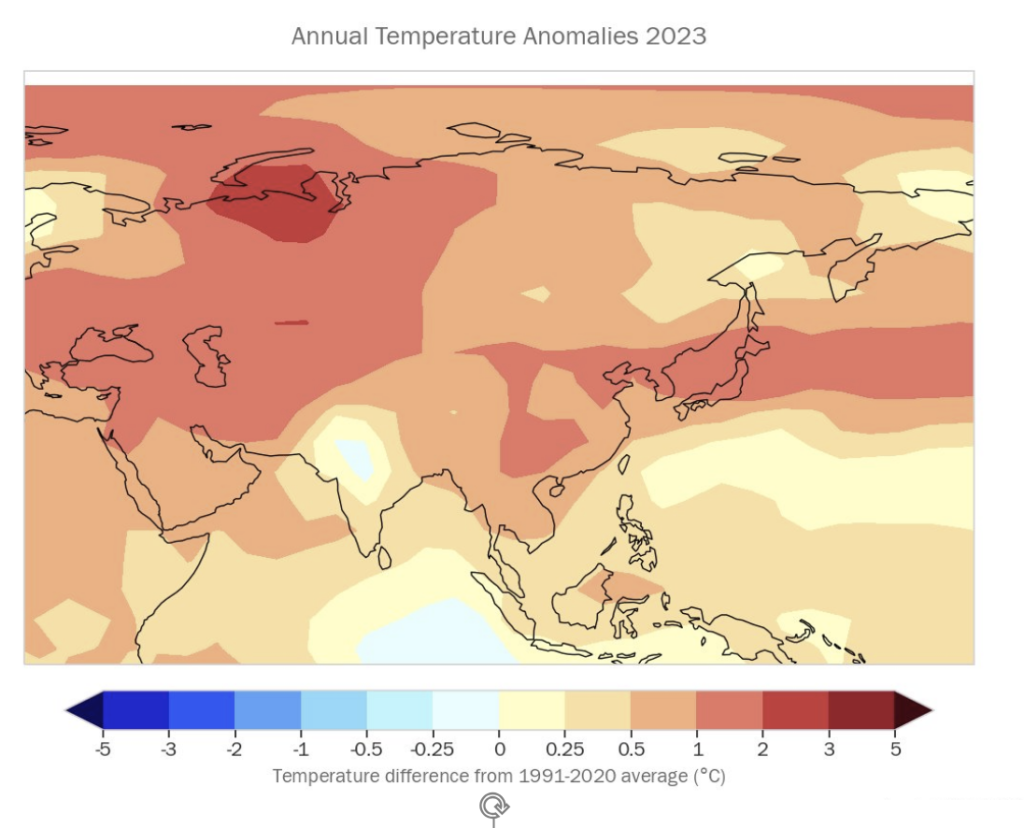

Temperatures

The annual mean near-surface temperature over Asia in 2023 was the second highest on record, 0.91 °C [0.84 °C–0.96 °C] above the 1991–2020 average and 1.87 °C [1.81 °C–1.92 °C] above the 1961–1990 average. Particularly high average temperatures were recorded from western Siberia to central Asia and from eastern China to Japan. Japan and Kazakhstan each had record warm years.

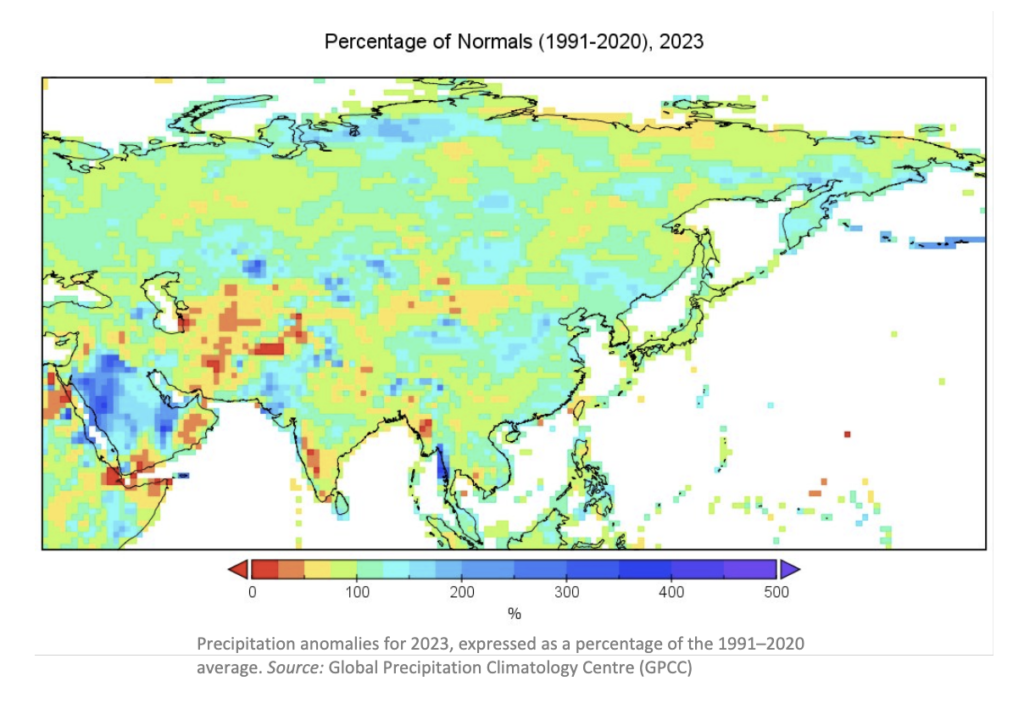

Precipitation

In 2023, precipitation was below normal in large parts of the Turan Lowland (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan); the Hindu Kush (Afghanistan, Pakistan); the Himalayas; around the Ganges and lower course of the Brahmaputra Rivers (India and Bangladesh); the Arakan Mountains (Myanmar); and the lower course of the Mekong River. Southwest China suffered from a drought, with below-normal precipitation levels nearly every month of 2023, and the rains associated with the Indian Summer Monsoon were below average.

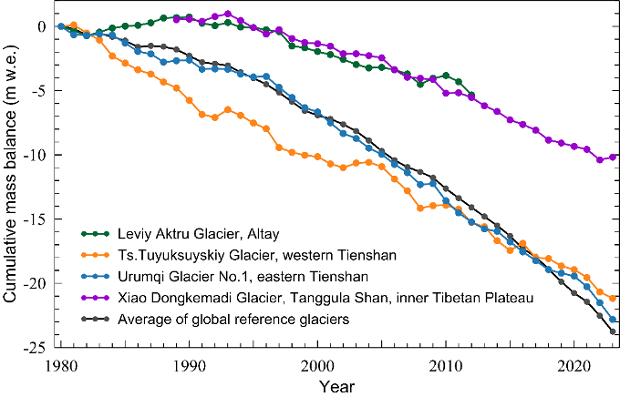

Cryosphere

The High-Mountain Asia region is the high-elevation area centred on the Tibetan Plateau and contains the largest volume of ice outside of the polar regions, with glaciers covering an area of approximately 100 000 km2. Over the last several decades, most of these glaciers have been retreating, and at an accelerating rate.

Twenty out of 22 observed glaciers in the High Mountain Asia region showed continued mass loss. Record-breaking high temperature and dry conditions in the East Himalaya and most of the Tien Shan exacerbated mass loss for most glaciers. During the period 2022–2023, Urumqi Glacier No. 1, in Eastern Tien Shan, recorded its second highest negative mass balance since measurements began in 1959.

Permafrost is soil that continuously remains below 0 °C for two or more years and is a distinctive feature of high-latitude and high-altitude environments. Monitoring carried out by the Russian Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring indicates that the most rapid thawing of permafrost is in the European north, the Polar Urals, and the western regions of Western Siberia. This is due to the continuing increase in air temperatures in the high latitudes of the Arctic.

Snow cover extent over Asia in 2023 was slightly less than the 1998–2020 average.

Cumulative mass balance (in metres water equivalent (m w.e.)) of four reference glaciers in the High Mountain Asia region and the average mass balance for the global reference glaciers.

Sea surface temperatures and ocean heat

The sea surface in the areas of the Kuroshio current system (west side of the North Pacific Ocean basin), the Arabian Sea, the Southern Barents Sea, the Southern Kara Sea, and the South-Eastern Laptev Sea is warming more than three times faster than the globally averaged sea surface temperature.

In 2023, the area-averaged sea surface temperature anomalies were the warmest on record in the North-west Pacific Ocean. The Barents Sea is identified as a climate change hotspot because ocean surface warming has a major impact on sea-ice cover, and there is a feedback mechanism in which loss of sea-ice in turn enhances ocean warming because darker sea surfaces can absorb more solar energy than the highly reflective sea-ice.

Warming of the upper-ocean (0 m–700 m) is particularly strong in the North-Western Arabian Sea, the Philippine Sea and the seas east of Japan, more than three times faster than the global average.

The writer of this article is Dr. Seema Javed, an environmentalist & a communications professional in the field of climate and energy