North America Heatwave Almost Impossible Without Climate Change : Attribution Study

The study was conducted by 27 researchers as part of the World Weather Attribution group

Last week’s record-breaking heatwave in parts of the US and Canada would have been virtually impossible without the influence of human-caused climate change, according to a rapid attribution analysis by an international team of leading climate scientists. Climate change, caused by greenhouse gas emissions, made the heatwave at least 150 times more likely to happen, the scientists found.

Pacific Northwest areas of the US and Canada saw temperatures that broke records by several degrees, including a new all-time Canadian temperature record of 49.6oC (121.3oF) in the village of Lytton – well above the previous national record of 45oC (113oF). Shortly after setting the record, Lytton was largely destroyed in a wildfire.

“What we are seeing is unprecedented. You’re not supposed to break records by four or five degrees Celsius (seven to nine degrees Fahrenheit). This is such an exceptional event that we can’t rule out the possibility that we’re experiencing heat extremes today that we only expected to come at higher levels of global warming,” said Friederike Otto, of Environmental Change Institute, Oxford University

“While we expect heatwaves to become more frequent and intense, it was unexpected to see such levels of heat in this region. It raises serious questions whether we really understand how climate change is making heat waves hotter and more deadly,” said Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

Every heatwave occurring today is made more likely and more intense by climate change. To quantify the effect of climate change on these high temperatures, the scientists analysed the observations and computer simulations to compare the climate as it is today, after about 1.2°C (2.2oF) of global warming since the late 1800s, with the climate of the past, following peer-reviewed methods. The extreme temperatures experienced were far outside the range of past observed temperatures, making it difficult to quantify exactly how rare the event is in the current climate and would have been without human-caused climate change — but the researchers concluded that it would have been “virtually impossible” without human influence.

“Climate change is making extremely rare events such as this one become more frequent. We are entering uncharted territory. The temperatures experienced in Canada last week would have broken records in Las Vegas or Spain. However, much higher temperature records will be reached if we don’t manage to stop greenhouse gas emissions and halt global warming,” said Sonia Seneviratne, Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zurich.

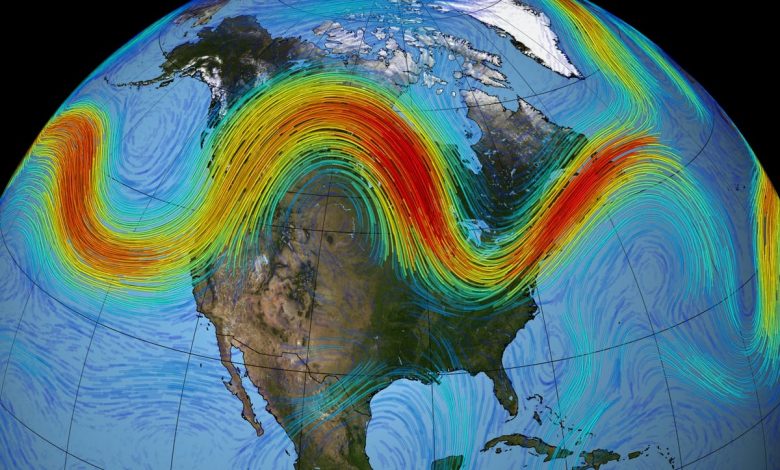

The researchers found two alternative explanations for how climate change made the extraordinary heat more likely. One possibility is that, while climate change made such an extreme heatwave more likely to happen, it remains a very unusual event in the current climate. Pre-existing drought and unusual atmospheric circulation conditions, known as the ‘heat dome’, combined with climate change to create the very high temperatures. In

this explanation, without the influence of climate change the peak temperatures would have been about 2°C (3.6°F) lower.

“Heatwaves topped the global charts of deadliest disasters in both 2019 and 2020. Here we have another terrible example — sadly no longer a surprise but part of a very worrying global trend. Many of these deaths can be prevented by adaptation to the hotter heat waves that we are confronting in this region and around the world,” said Maarten van Aalst, Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and University of Twente.

“In the United States, heat-related mortality is the number one weather-related killer, yet nearly all of those deaths are preventable. Heat action plans can reduce current and future heat-related morbidity and mortality by increasing preparedness for heat emergencies, including heatwave early warning and response systems, and by prioritizing modifications to our built environment so that a warmer future does not have to be deadly,” said

Kristie L. Ebi, Center for Health and the Global Environment, University of Washington.

Until overall greenhouse gas emissions are halted, global temperatures will continue to increase and events like these will become more frequent. For example, even if global temperature rise is limited to 2°C (3.6°F), which might occur as soon as 2050, a heatwave like this one would occur about once every 5 to 10 years, the scientists found.

An alternative possible explanation is that the climate system has crossed a non-linear threshold where a small amount of overall global warming is now causing a faster rise in extreme temperatures than has been observed so far — a possibility to be explored in future studies. This would mean that record-breaking heatwaves like last week’s event are already more likely to happen than climate models predict. This raises questions about how well current science can capture the behaviour of heat waves under climate change.

The event sends a strong warning that extreme temperatures, far outside the temperature range currently expected, can occur at latitudes as high as 50°N, a range that includes all of the contiguous US, France, parts of Germany, China and Japan. The scientists warn that adaptation plans should be designed for temperatures well above the range already witnessed in the recent past.

“This event should be a big warning. Currently we do not understand the mechanisms well that led to such exceptionally high temperatures. We may have crossed a threshold in the climate system where a small amount of additional global warming causes a faster rise in extreme temperatures,” said Dim Coumou, Institute for Environmental Studies (VU Amsterdam), Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI).

“It is amazing to see what we achieved in just over a week, with 27 scientists and local experts involved in this rapid attribution from research institutes and meteorological agencies. Combining knowledge and model data from around the world raises confidence in the extensive study results,” said Sjoukje Philip & Sarah Kew, study leads, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI).

The study was conducted by 27 researchers as part of the World Weather Attribution group, including scientists from universities and meteorological agencies in Canada, the US, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, France and the UK.

Views expressed here are those of Dr. Seema Javed, a known Environmentalist, Journalist and Communications